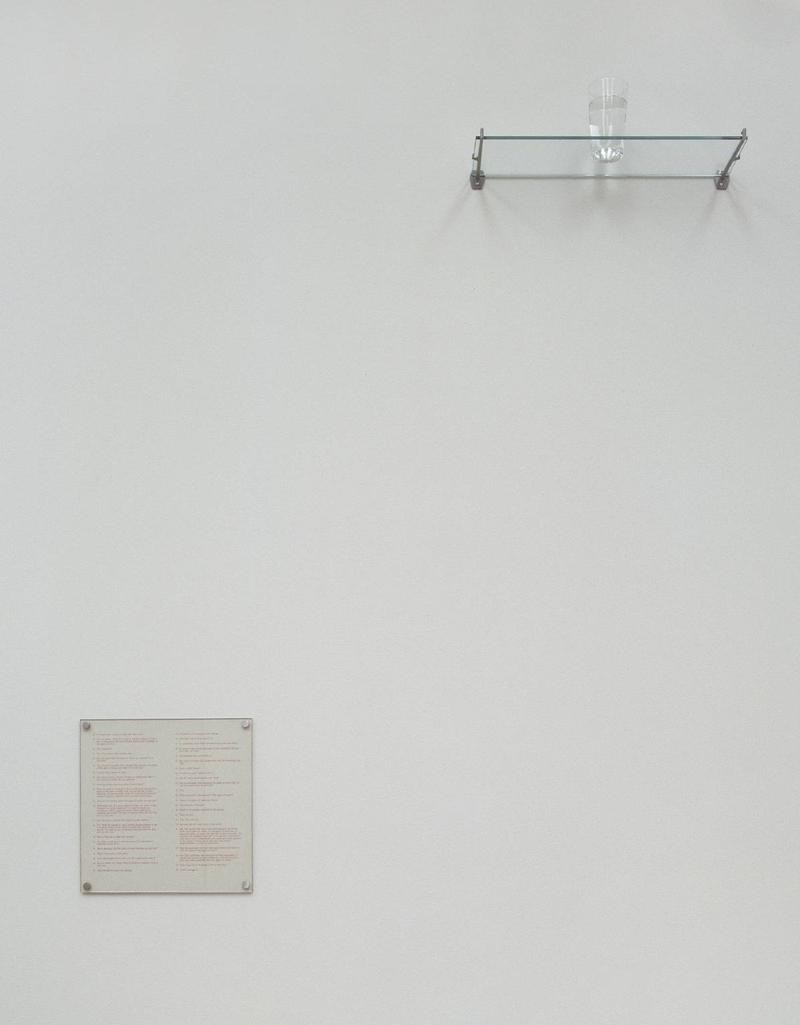

‘An Oak Tree’, Michael Craig-Martin, 1973

An Oak Tree

There was a minor movement in poetry called Martian Poetry, which sought to ‘break the grip of the familiar’ by describing ordinary things in unfamiliar ways – the world described as if through the eyes of a Martian. Poet Craig Raine describes the act of reading a book, as if observing this strange act for the first time:

mechanical birds with many wings

perch on the hand

cause the eyes to melt

or the body to shriek without pain

In An Oak Tree (pictured), artist Michael Craig-Martin attempts to jolt our conception of the world by telling us that “an oak tree is physically present but in the form of the glass of water.” His assertion forces us to come to terms with a violent disjunct between what we see and what we’re told.

These ideas hold interesting lessons for the designer who seeks to make visible those aspects of our lives rendered invisible by habits of behaviour.

Such concerns are present in the work of the Psychogeographers who, in the 1950’s, described their endeavours as “a whole toy box full of playful, inventive strategies for exploring cities…just about anything that takes pedestrians off their predictable paths and jolts them into a new awareness of the urban landscape.”

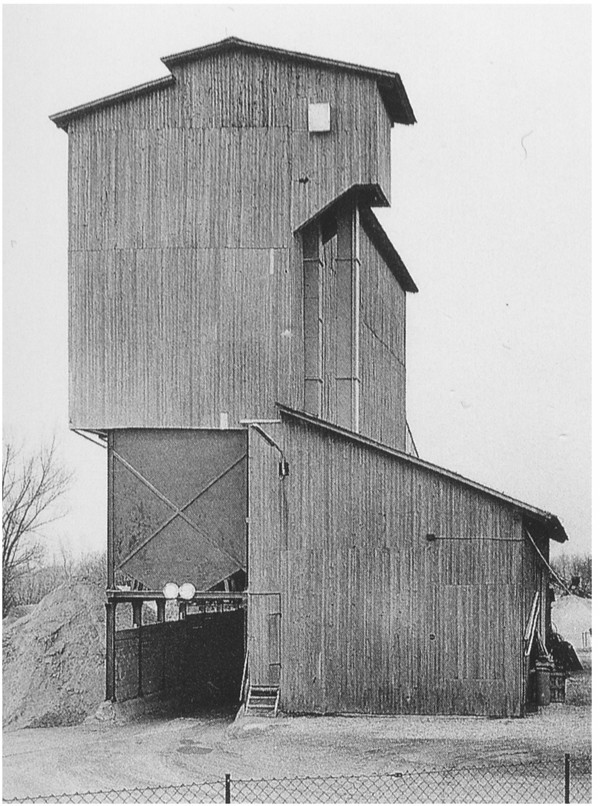

‘Gravel plant’, Kirchham-bad Füssing, Germany, Bernd and Hilla Becher, 1991

Bernd and Hilla Becher

We have always been charmed by this Becher photograph. The building’s composition is elegant, and yet it has clearly been built without aesthetic consideration. It has an informal charm that has presumably resulted from a series of functional decisions. It reminds us that it’s often best just letting something be what it needs to be, without trying to smooth or sanitise what might otherwise have a character all of its own. We often talk about this photo as an expression of what we refer to as some kind of ‘organic functionalism’.

‘We write the city; the city writes us’, Manifesto Diagram, Aa, 2012

Manifesto Diagram

We write the city; the city writes us. When Architecture architecture first launched in 2012, Architect Victoria ran a special edition focussing on emerging practices and their manifestos. Opting to represent our ideas visually, we spent quite some time discussing our values and interests in architecture, synthesising these into a set of interrelated ideas represented by this diagram.

We are interested in the ways that cities shape people and vice-versa. We feel that architecture has a role to play in encouraging broad, democratic participation in the formation and transformation of the built environment.

For many of us daily life is so habitual that we are blind to the environments that shape us. The places where we live, work, sleep, learn, meet, relax, retreat (etc.) have a profound impact on our mental and physical health, as well as our capacity to form social networks, self-reflect and grow.

We are interested in the idea that by making strange those parts of our lives that have become over-familiar, we can pull the rug of expectation out from under the collective foot, encouraging more conscious engagement with the built environment and its effects.

Each day we perform familiar rituals, and yet each day we perform them slightly differently, consciously or otherwise: methods for extracting honey from the jar; procedures for leaving a room; the way we move toothpaste around in our mouths – actions which, in small ways, contribute to our sense of self. In making slight adjustments to these actions over time, we make strange or particular what is otherwise familiar and banal.

We do the same when we design. We make manifest our interpretation of human action. We represent it and affect it. We create a version of the world that is unique and so at some level, strange. In our work we try to remain conscious of this act and of its consequences, designing homes, schools, workplaces and public spaces that encourage participation, interaction and play.

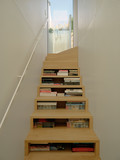

Staughtons’ Corner, Warracknabeal

Staughtons' Corner

This project demonstrates the power of a geometric aberration. Located in Warracknabeal, the birthplace of Nick Cave, the original house was designed by Peter Staughton, later extended by his sons Stephen and James. Where the work of the two generations meet, their geometries find a moment of distinct discomfort. Rather than seeking harmonious resolution, brothers Staughton lean-in, brutally highlighting the disjunct with a coat of retro-reflective film to catch the headlights of passing cars.

The restless eye, unable to disengage, continually returns to the awkward angles of this corner, trying to make sense of it. A lesson in the power of disharmony. Nick would be proud.

‘Triangular pavilion with cicular cut-outs, variation H’, Dan Graham, 2008

‘Feelings are facts’, Olafur Eliasson, 2010

‘The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses’ by Juhani Pallasmaa, 1996

The Eyes of The Skin

In The Eyes of the Skin, Juhani Pallasmaa laments architects’ tendency to preference vision over the other senses. He advocates for an architecture that is visually indistinct, that we may become sensorially immersed in our environments. Artist Olafur Eliasson seems to align himself with this thesis, creating works of spectral saturation and immersion. As the visual realm closes in, participants draw upon the other senses to understand the space they occupy. Dan Graham similarly plays tricks with reflectivity and transparency to blur spatial information, creating intriguing environments from very simple geometries.

Let the flesh, imperfect, see

What eyes, precise, forget.

‘Presidency II’, Thomas Demand, 2008

Thomas Demand

Unless you’re familiar with his work, it isn’t immediately obvious whether Thomas Demand’s photographs are of a real or a constructed world. His creations so closely approximate reality, it’s hard to be sure. Demand carefully reconstructs real scenarios from paper and card, removing any direct signs of human occupation. He then photographs the life-sized model and destroys it.

Demand’s photography is unassuming, so when it catches you, it does so by surprise. It starts you questioning the fibre and function of other aspects of your environment. If strangeness lurks in such quiet, small and unassuming ways, then perhaps it is all around me. Perhaps I need to look a little closer. I must remain alert.

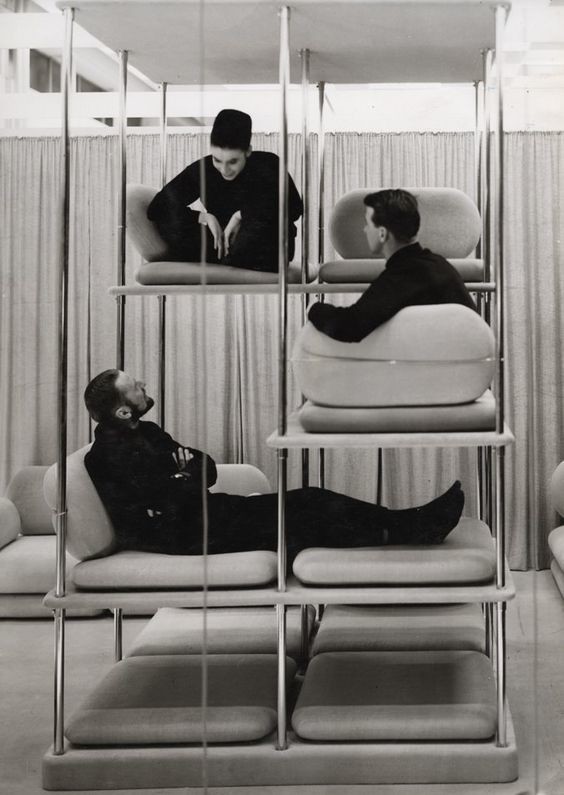

Verner Panton, Multi-Level Lounger, 1964

The Multi-Level Lounger

Verner Panton’s simple yet elegant ‘multi-level lounger’ communicates so much of what we are striving for in our architecture. It stands as a built diagram of the communal life, where people are brought together in a three-dimensional matrix of spaces: adjacent, above, across, below.

It represents the diametric affordances of all good architecture: both the opportunity to gather, and to retreat. To gather with friends, colleagues, family; or to retreat from the world into a place of quiet comfort. It’s a provocation for what might be possible in the arrangement of our homes, our workplaces, our public spaces, both at the macro scale and the micro.

It is also an exemplar of clarity in form-making – doing no more than it needs. And yet, there’s a sparkle in its eye. It isn’t like anything else we know. Just looking at it, we begin to imagine our lives differently.