The Scoop

There’s a revolution afoot at the University of Melbourne. The future of its Parkville campus is a university teeming with student life. Not only a place for academic excellence, but a place of social exchange and cultural nourishment, where a diverse student corpus revels in its self-determination.

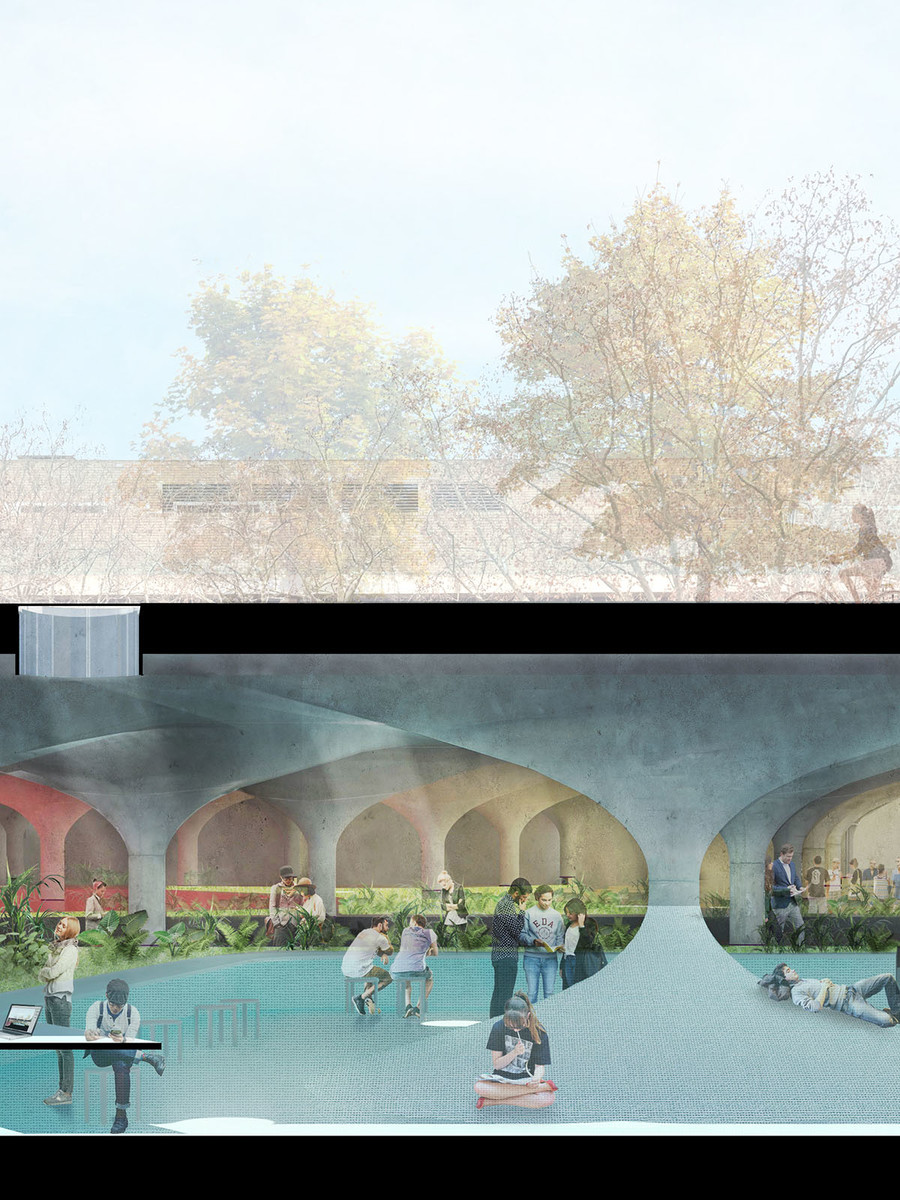

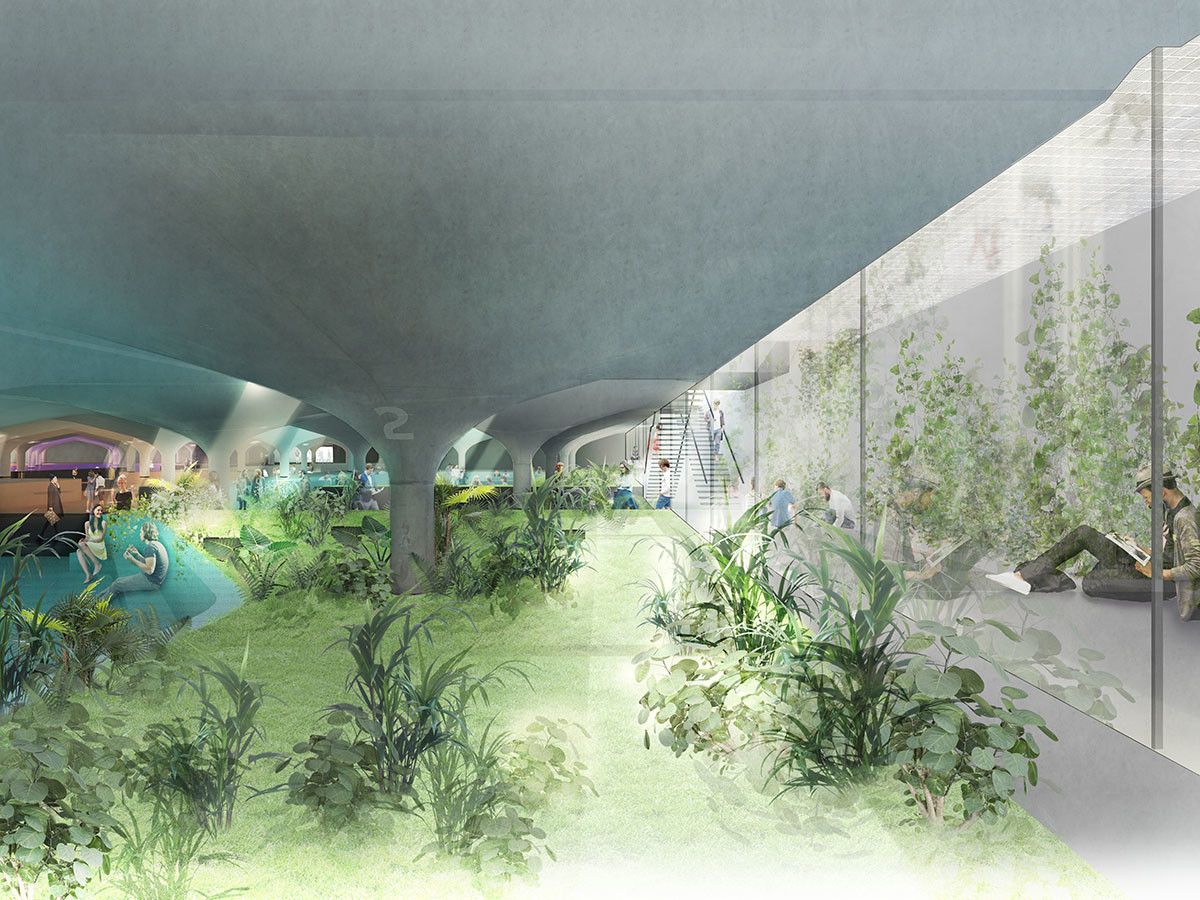

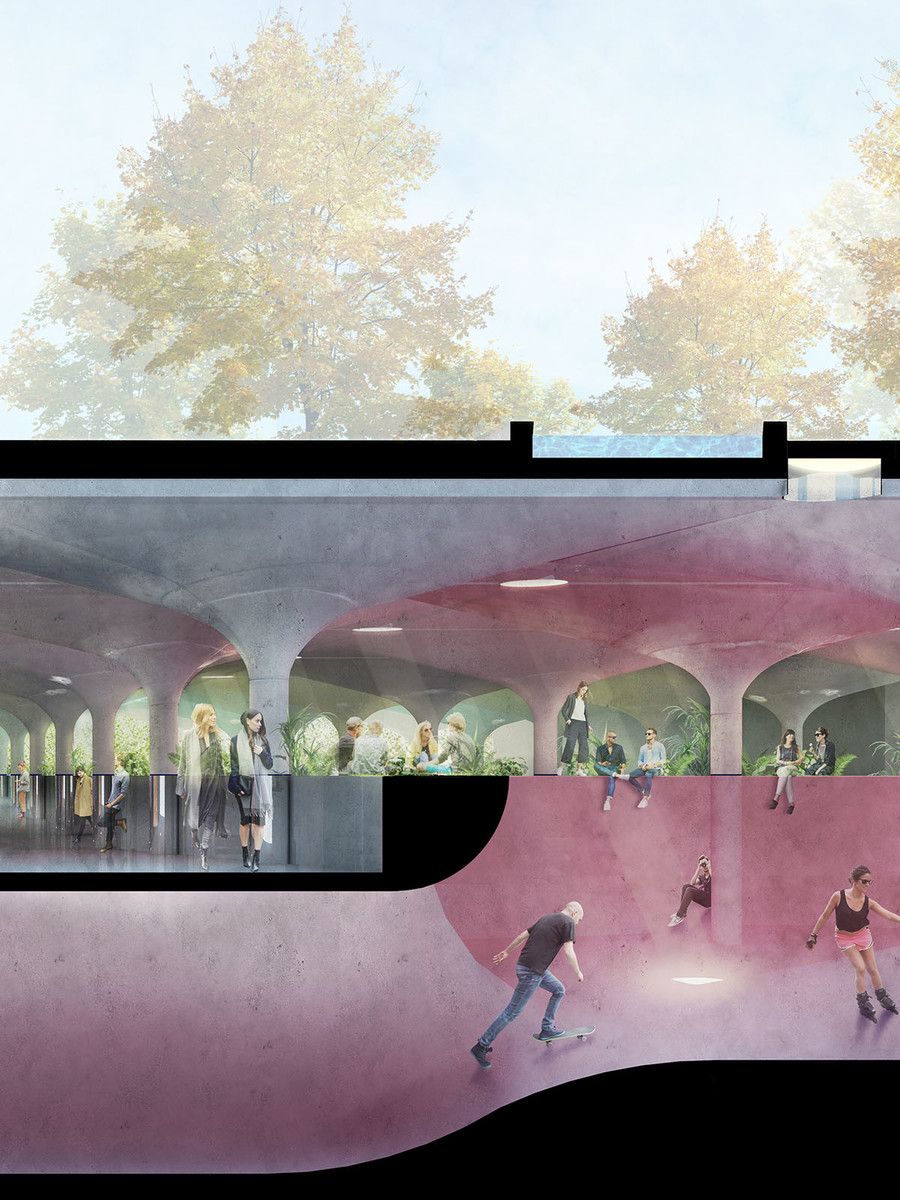

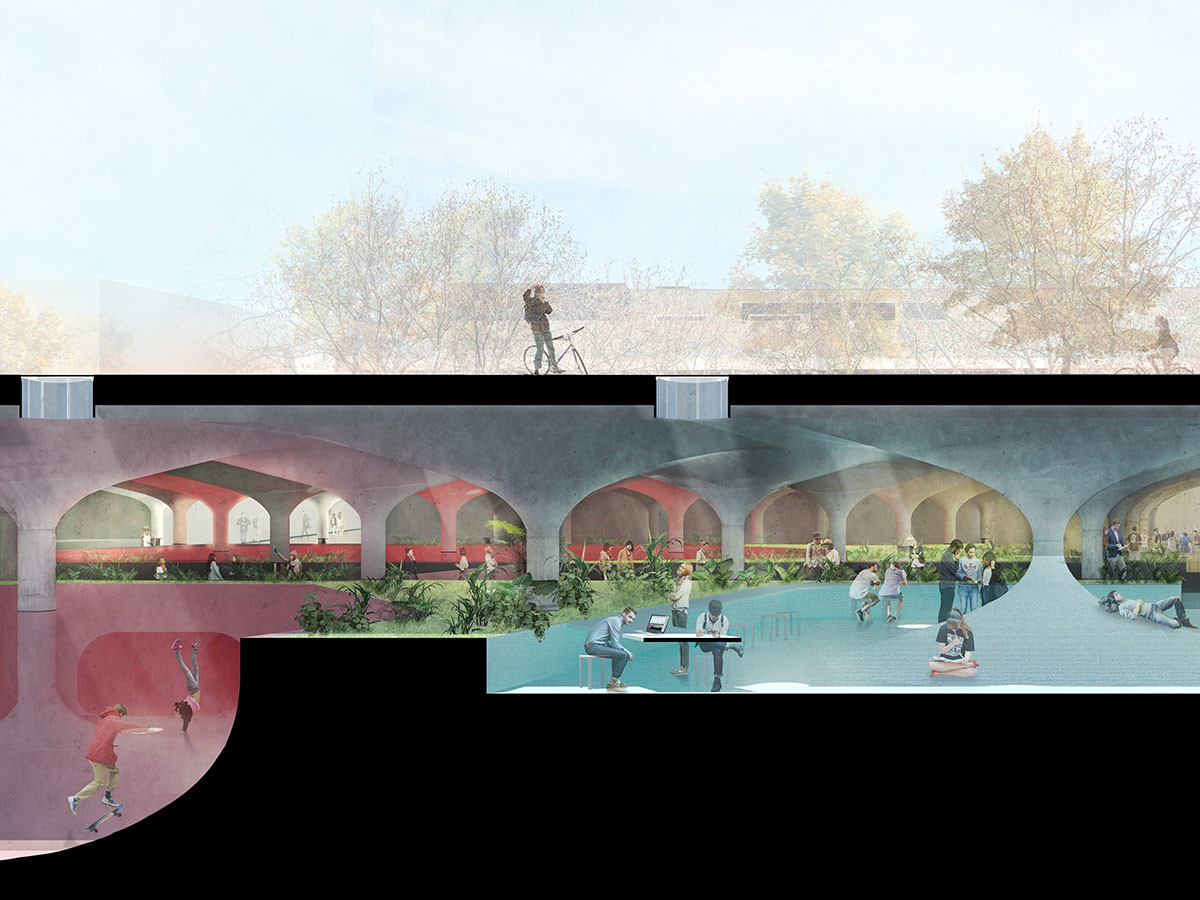

In the heart of the student campus is a crypt of unrealised grandeur. Once an underground carpark, its sweeping field of parabolic vaults promises so much more. Raw concrete arcs out of the ground in defiance of gravity, an expression of aspiration and daring. More than an arcade, a colonnade, or a cloister, this is a civic space – everyone has sensed it. A place of earthly means and heavenly ambition. Something of a grotto; something of a church.

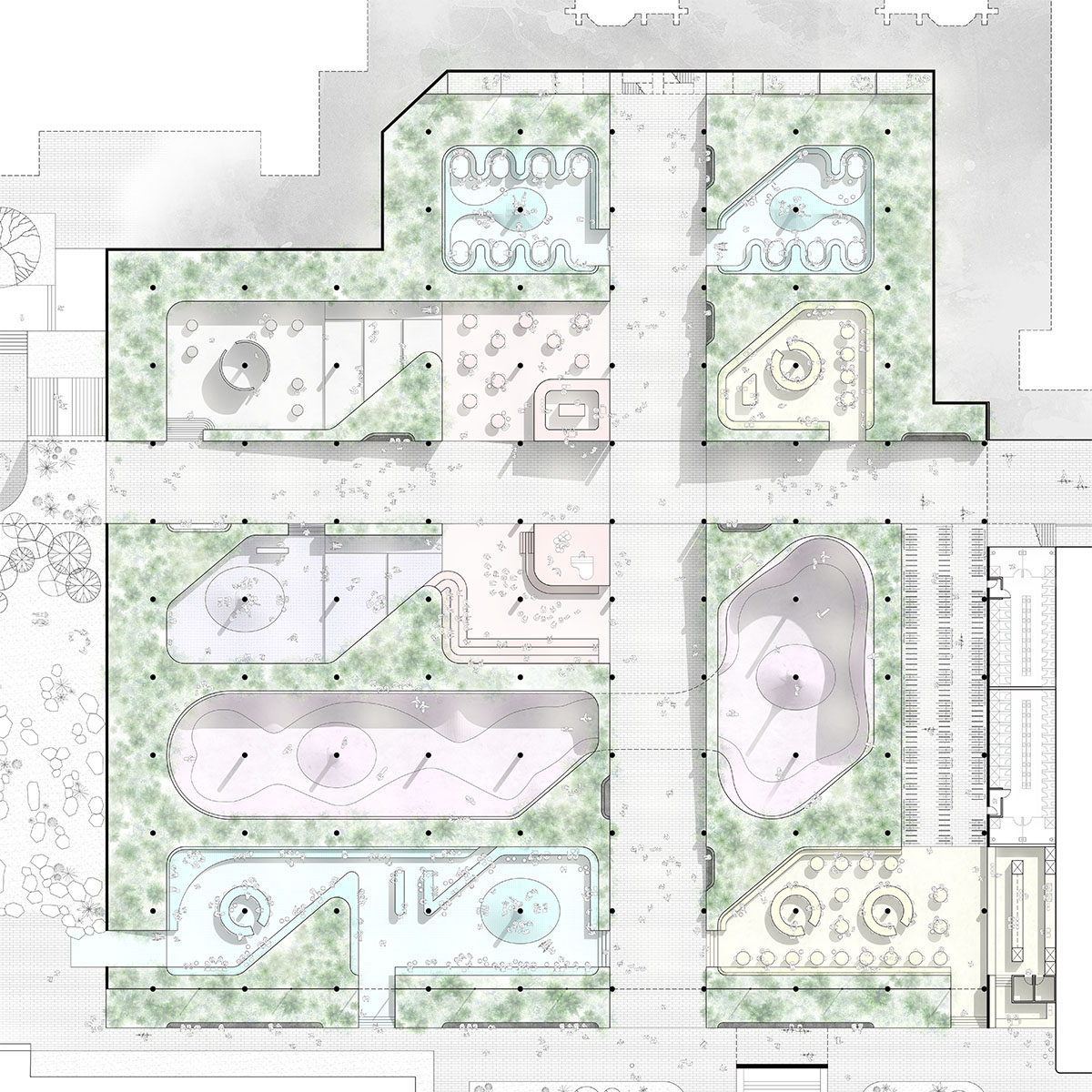

It’s almost as if Loder & Bayly knew there was more to come. The ambition of their design exceeds the brief. Providing the university with a breathtaking roof, they provoke: ‘and what should become of the spaces below?’. Our response: let’s scoop them out. Together with students, we’ll uncover the promise of what lays beneath: the future of campus life.

| Client | University of Melbourne |

| Completed | 2018 (feasibility) |

| Budget | $25m |

| Details | See floor plan |

‘We write the city; the city writes us’, Manifesto Diagram, Aa, 2012

‘We write the city; the city writes us’, Manifesto Diagram, Aa, 2012

Manifesto Diagram

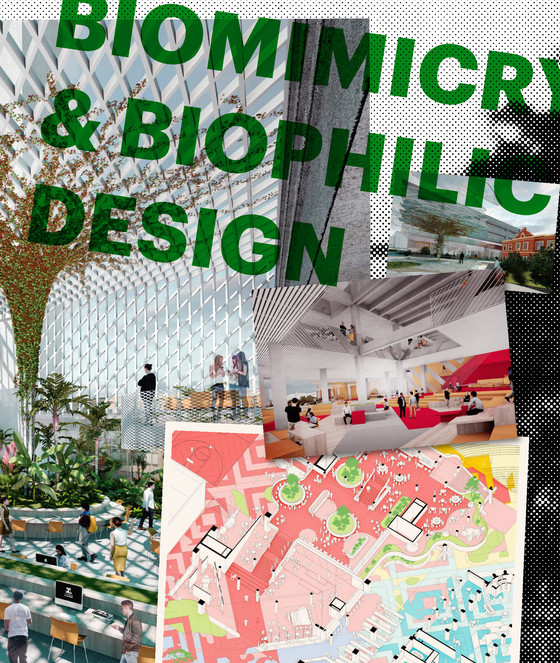

We write the city; the city writes us. When Architecture architecture first launched in 2012, Architect Victoria ran a special edition focussing on emerging practices and their manifestos. Opting to represent our ideas visually, we spent quite some time discussing our values and interests in architecture, synthesising these into a set of interrelated ideas represented by this diagram.

We are interested in the ways that cities shape people and vice-versa. We feel that architecture has a role to play in encouraging broad, democratic participation in the formation and transformation of the built environment.

For many of us daily life is so habitual that we are blind to the environments that shape us. The places where we live, work, sleep, learn, meet, relax, retreat (etc.) have a profound impact on our mental and physical health, as well as our capacity to form social networks, self-reflect and grow.

We are interested in the idea that by making strange those parts of our lives that have become over-familiar, we can pull the rug of expectation out from under the collective foot, encouraging more conscious engagement with the built environment and its effects.

Each day we perform familiar rituals, and yet each day we perform them slightly differently, consciously or otherwise: methods for extracting honey from the jar; procedures for leaving a room; the way we move toothpaste around in our mouths – actions which, in small ways, contribute to our sense of self. In making slight adjustments to these actions over time, we make strange or particular what is otherwise familiar and banal.

We do the same when we design. We make manifest our interpretation of human action. We represent it and affect it. We create a version of the world that is unique and so at some level, strange. In our work we try to remain conscious of this act and of its consequences, designing homes, schools, workplaces and public spaces that encourage participation, interaction and play.